The history of punk rock music, and especially British punk rock, is complex and multifaceted. It reflects not only a musical movement but also a cultural and social phenomenon that has an enduring legacy, both musically and in terms of popular culture. It’s interesting to look back on the evolution of music genres, and there’s no better example of this than punk rock. It’s also true that revolution may be a more appropriate term in punk’s case.

Now, there is always an arbitrary nature to these things, but I’m going to argue that punk’s ancestry lies in the tumultuous climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s. During this period, a sense of rebellion was brewing. Youth culture started to push back against the established norms, fuelled by political dissatisfaction and a yearning for authenticity. At its outset, this was the era of peace and love; there was a distinctly non-violent vibe to it all – Altamont apart.

However, at the same time, we had the precursors to punk. They were a mix of garage rock, proto-punk, and early hard rock bands that played with an unrefined edge that mainstream music often lacked. Bands like The Stooges, MC5, and the New York Dolls were among those at the forefront, diverging from psychedelic rock and embracing simpler, harder sounds. Even the Beatles, supposedly disliked and dismissed by the Sex Pistols, demonstrated a darker, harder edge on certain tracks.

This period wasn’t just about the music, though. The social and political unrest of the time, with movements against the Vietnam War and for civil rights, added an urgency that echoed through the chords and lyrics. During this period, music was arguably as much about attitude as it was about the specific sound – a combination of fashion, politics, and sonic defiance.

As the 1970s kicked in, the ground was fertile for a new form of music that would capture the growing discontent of young people. That’s where the story of punk truly starts to accelerate. In the mid-1970s, across the pond from its ancestors, a new scene began to take form. This scene was raw, it was loud, and it was unequivocally punk.

The Explosion of Punk Music: A Defiant Cry in the Mid-1970s

In the mid-1970s, cities like New York and London became the epicentres of a raw, fast-paced brand of music that would come to be known as punk rock. Echoing the dissatisfaction of youth culture with the status quo, punk emerged as much more than just a musical genre; it was a bold statement against societal norms and commercialism in music.

Bands like the Ramones and the New York Dolls in the States, as well as The Sex Pistols and The Clash in the UK, began churning out songs that were short, aggressive, and unpolished. These pioneering acts rejected the complex solos and overproduced sounds prevalent in the mainstream music of the time, opting instead for simplicity and directness.

This period also saw the creation of what would become anthems of the punk movement. Tracks such as Blitzkrieg Bop by the Ramones and Anarchy in the UK by The Sex Pistols encapsulated the ethos of punk coming in around three minutes. These songs were rallying cries for a demographic that felt unheard.

Alongside the music, a burgeoning punk scene started to flourish in clubs like CBGB in New York City, where bands could play original material to like-minded individuals. These venues became incubators for the punk scene, fostering a sense of community among outcasts and cultivating an environment that encouraged self-expression and rebellion.

As the 1970s waged on, punk’s influence crept across the Atlantic. The UK, experiencing an economic downturn, rising inflation, and rising unemployment, proved fertile ground for the defiant message of punk to resonate. The rawness and immediacy of the music served as a vehicle for British youth to voice their frustrations and disillusionment.

The arrival of punk from the US set the stage for what would be a profound cultural phenomenon in the UK. It would infiltrate fashion, language, and lifestyle, cementing punk not only as a musical genre but as a cultural movement. We are now set to learn a little about the edgy, innovative, and sometimes violent chapter of UK punk. Music would take on a more overtly political stance and become synonymous with resistance and anti-establishment sentiment.

Punk Invades the UK: A Cultural Phenomenon

By the mid-to-late 1970s, punk exploded in the United Kingdom, transforming from a musical genre to a cultural phenomenon, fuelled by economic discontent and a youth eager to express their disillusionment. It became synonymous with a form of resistance to the status quo, an infectious energy that was differently nuanced from its American counterpart. It was raucous, and unapologetic, and went beyond the music to influence fashion, art, literature, and politics.

Key bands like the Sex Pistols, The Clash, and Buzzcocks not only created music that was raw and stripped-down but also sparked conversations with their politically charged lyrics and direct social commentary. Their sound and message resonated with the frustrations of the British youth, voicing anger and dissent against socioeconomic issues.

The UK punk scene was further characterized by its distinct fashion, led by designers like Vivienne Westwood. It embraced elements like spiked hair, safety pins, and ripped clothing – punk wasn’t just heard; it was seen and felt. Westwood’s shop Sex, which she owned with her then-husband Malcolm McLaren was almost a punk hub in the earliest days of punk in the UK.

All four of the original members of the Sex Pistols had an association of one sort or another with the boutique. For example, bass player Glen Matlock was a Saturday sales assistant on Saturdays. In August 1975, the nineteen-year-old John Lydon auditioned for the group by singing along to Alice Cooper’s I’m Eighteen on the jukebox. Other notable patrons included occasional assistant Chrissie Hynde, Adam Ant, Marco Pirroni, Siouxsie Sioux, Steven Severin (later Siouxie Sioux’s bassist) and other members of the Bromley Contingent.

Venues such as the 100 Club on Oxford Street in London became influential punk hotspots and as part of a two-night ‘Punk Special’ there, the Sex Pistols played on the first night, Monday, 20 September 1976. Also featuring that first night, were Subway Sect, Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Clash. The second night saw Stinky Toys, Chris Spedding & The Vibrators, The Damned and Buzzcocks.

In the crowd during the Punk Special, were the likes of Paul Weller, Shane MacGowan (later of the Nipple Erectors and the Pogues), Viv Albertine of the Slits, Chrissie Hynde (later of the Pretenders), Jah Wobble (later of PiL), and Gaye Advert and T. V. Smith (both of The Adverts).

The record label EMI signed the band on a two-year contract on 8 October 1976 and they were soon in the studio at Wessex Sound, at Highbury New Park in London, recording what would be their first single Anarchy in the UK. The track was released on 26 November 1976.

Within a week, the event followed that was perhaps to highlight the attitude that punk brought to the UK and would leave an indelible mark on British culture. It served not only to demonstrate exactly what the establishment thought it feared and disliked about punk rock but also to vindicate exactly what the Sex Pistols and their fans were all about.

Bill Grundy: An Unintended Spark that Lit the Fuse

The appearance of the Sex Pistols on the Thames Television Today show hosted by Bill Grundy on Wednesday 1 December 1976, is one of the most infamous moments in television history. The interview became a pivotal event in the rise of punk rock and is often cited as a landmark moment in the cultural history of the 1970s.

The band had not been originally booked to appear on the Today. Until Freddie Mercury’s toothache had got too much for him, the band Queen was due to appear on the show. So, a late phone call was made, and the Sex Pistols agreed to stand in. The interview began relatively calmly with Bassist Glen Matlock enjoying some verbal jousting with Grundy, but it quickly escalated into chaos and controversy.

Other members of the band, especially guitarist Steve Jones (wearing a tee-shirt adorned with a photocopied image of a pair of breasts) and Johnny Rotten, used explicit language throughout the interview. Their behaviour was confrontational and defiant and was provoked by Grundy, who may or may not have been drunk. The interview set the telephone lines into Thames Television buzzing as viewers rang in to express their outrage and condemnation, particularly from more conservative quarters.

Following the interview, the Sex Pistols became a focal point of media scrutiny and controversy. For example, the Daily Mirror chose to paraphrase the Bard with its headline “The Filth and the Fury,” highlighting what some might argue was the over-the-top response to the show. Others might have agreed with the Mirror, arguing that exposing children to swearing as they ate their tea, was unacceptable. Either way, the event contributed to the band’s notoriety and, in a way, helped fuel the punk movement’s anti-establishment image.

The Sex Pistols: A Trinity of Record Labels

Shortly after the new year, EMI had its Epiphany, and the band were dropped on 6 January 1977. The interview with Grundy may not have been the straw that broke the camel’s back – that was probably when, en route to the Netherlands, they indulged in a hungover fit of spitting and throwing up – but it cannot have helped.

On 10 March in Jubilee year, the Sex Pistols signed with their new record label A&M in front of Buckingham Palace. Later that year, on 7 June, the band sailed down the Thames on a boat appropriately named Queen Elizabeth. The intention had been to use the trip to publicise their second single, God Save the Queen, which had been recorded in October the previous year.

Possibly coincidentally, it wasn’t released until the end of May with the country in full Silver Jubilee preparation mode; the band were by now on their third record label having been dropped by A&M less than a week after signing for them. Consequently, it was released on A&M and their new label, Richard Branson’s Virgin.

Work continued throughout Spring and Summer of 1977 on the rest of the band’s album, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols which was released on 28 October 1977 complete with the song EMI – an anti-paean to the label. Three months after the album’s release, in January 1978, Johnny Rotten announced the Sex Pistols’ break-up. It may have been unilateral, but he did not perform with the group again until their first reunion in 1996.

The DNA of Punk: DIY Ethos and the Independent Spirit

In the DNA of punk music lies an ethos of do-it-yourself (DIY) spirit which has forever disrupted the landscape of music production. Punk wasn’t just about the sound; it was also about the way that sound reached its listeners. Unsatisfied with the constraints of mainstream record labels, punks took matters into their own hands.

This meant recording in basements, distributing tapes through zines, and using word-of-mouth to amplify their message. Interestingly, of the bands that featured on the bill of the 100 Club Punk Special, only The Damned (Stiff Records) and Subway Sect (Rough Trade) were signed to labels that could be described as independent. For example, Siouxsie Sioux and her Banshees were signed to Polydor Records and The Clash to Columbia.

The emergence of independent labels was pivotal in punk’s evolution. The aforementioned Stiff Records and Rough Trade are both notable British record labels with significant histories in the music industry. Stiff Records was founded in 1976 by Dave Robinson and Jake Riviera.

Born during the punk era in the United Kingdom, the label gained a reputation for its irreverent and independent spirit. It released punk and new wave music from the likes of Elvis Costello, Ian Dury and the Blockheads, The Damned, Nick Lowe, and The Pogues. Elvis Costello’s debut album, My Aim Is True, was among the first releases on the label. In a slight departure in the musical genre, if not artist attitude, Stiff also released the first 5 albums by Madness, although their singles were released on Two-Tone Records.

Stiff was known for its innovative marketing strategies, such as the “Be Stiff” tour and the use of quirky slogans and graphics. The label was a true embodiment of the DIY ethos that punk engendered.

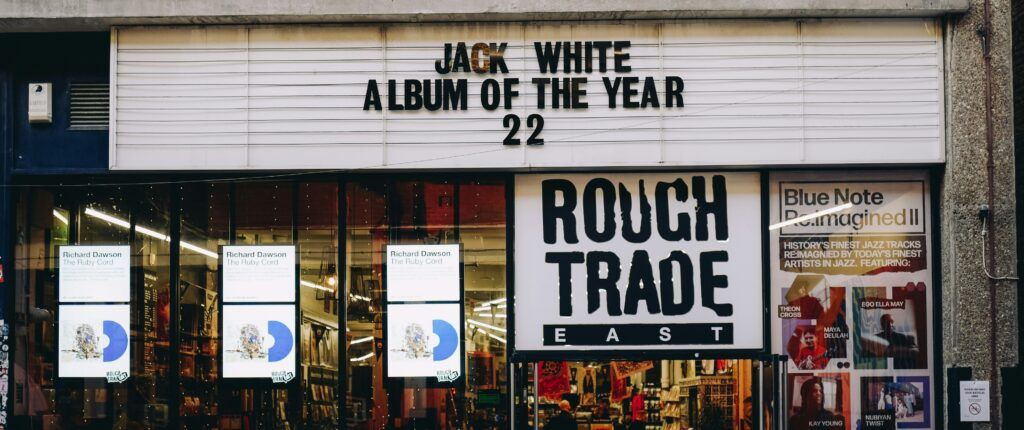

Rough Trade was founded, first as a London record shop by Geoff Travis in 1978, before expanding into a record label. It was another label which played a crucial role in the post-punk and indie music scenes. The label signed influential and eclectic artists, from The Fall and Scritti Politti to perhaps most famously, The Smiths.

Like Stiff Records, Rough Trade maintained an independent and alternative ethos. The label became synonymous with supporting and promoting independent and groundbreaking music. In addition to the record shop and label, Rough Trade Records was also a distribution company, contributing to the distribution of many other independent labels and artists.

Both labels have left a lasting impact on the music industry, each contributing to the development of diverse musical genres and fostering a spirit of independence and innovation. While Stiff Records was more directly associated with the punk and new wave movements, Rough Trade became a key player in the post-punk and indie scenes.

Both labels played important roles in shaping the landscape of British music in the immediate aftermath of punk rock. Perhaps slightly paradoxically, although this pair were the embodiment of punk’s anti-establishment stance, they were also businesses; albeit ones which created a platform for bands that might otherwise remain unheard.

Today, the legacy of punk’s independent spirit is evident. The willingness to challenge the status quo, to create without permission, and to embrace a community-driven approach is apparent in various music genres. Modern artists still lean on the principles laid out by the pioneering punks, ensuring that the heart of DIY and in-your-face independence continues to beat strong in the music world.

In essence, the decaying flesh of punk rock has nourished a whole industry standard. Now, bedroom producers release their tracks to global audiences with just a few clicks, and indie labels function with autonomy that the pioneers of punk might have only dreamed about. This is the mark that punk has left on music. It is a vehicle for self-expression which transcends time, technology, and genre. The DIY sentiments and attitude that once gave rise to inter-generational conflict still resonate even if punk rockers now need to pull the most extraordinary shapes to put their socks on.

Hi, I am a millennial and I mostly just remember 90s punk. My parents liked the oldies but I don’t recall and punk in there. I’m from Canada though. I remember punk became more popular in the later 90s and after that I just stopped caring because music has gone downhill since in my opinion.

Thanks for your comment, Jake. I’m not sure what I understand by the term 90s punk 😉

For me, what I refer to as punk rock is a British phenomenon borne out of the attitude of American groups like the Stooges, the MC5s, and the Ramones to name but three. It was very short-lived, from 1976 until about 1980 – bands like the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Damned, Buzzcocks and a few others.