In 1893, Carl Lindström, a Swedish inventor living in Berlin, Germany founded a company to produce, phonographs (or gramophones). It soon diversified into producing shellac records and soon it had a suite of record labels, one of which, Parlophon was founded in 1896.

The British Branch of Parlophon was established as Parlophone in August 1923 under the auspices of A&R man Oscar Preuss. It soon established a reputation as a jazz label with some of its early releases from the likes of Ray Miller’s Medley Boys, Sam Gould/Harry Jentes and Robert Carr.

Four years later, Parlophone was acquired by the Columbia Gramophone Company when it took a controlling interest in the Lindström company. It soon became part of EMI (Electric and Music Industries) when Columbia Gramophone merged with the Gramophone Company.

Moving into the 1950s, Preuss first hired and then promoted a producer by the name of George Martin. Throughout the fifties, Parlophone specialised in mainly classical music, cast recordings, and regional British music. Martin also expanded Parlophone’s oeuvre into novelty and comedy records.

For example, 1958 saw the release of an album of Peter Sellers performing various comedy, parodical and satirical numbers. Somewhat surprisingly, the album performed well, reaching number three in the UK Albums Chart in 1958.

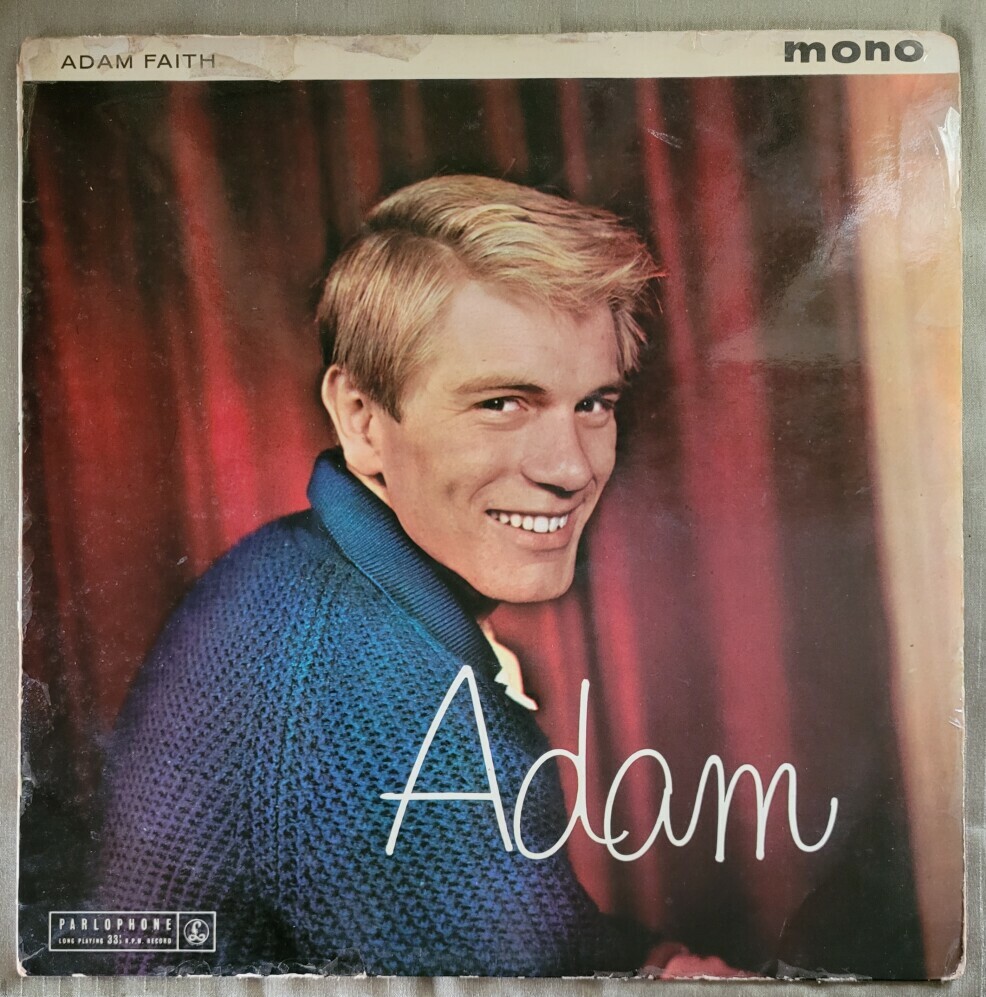

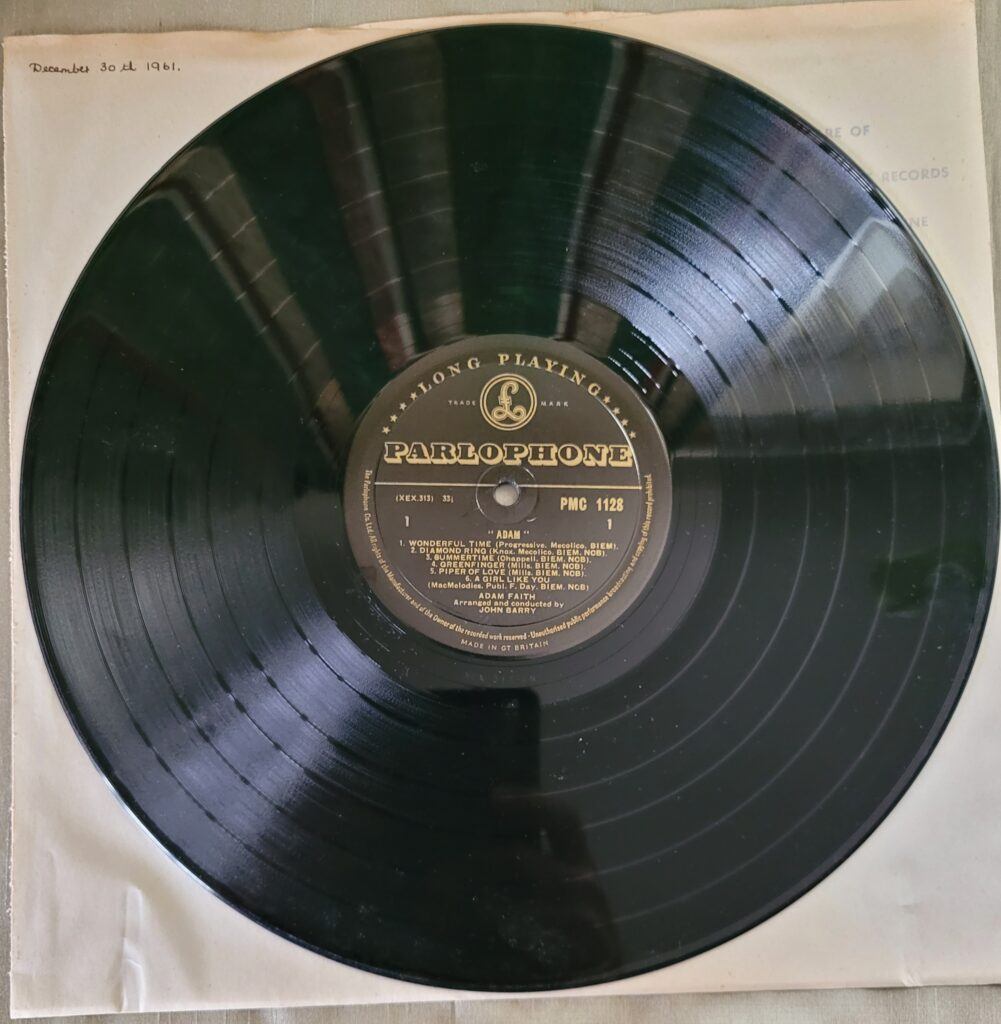

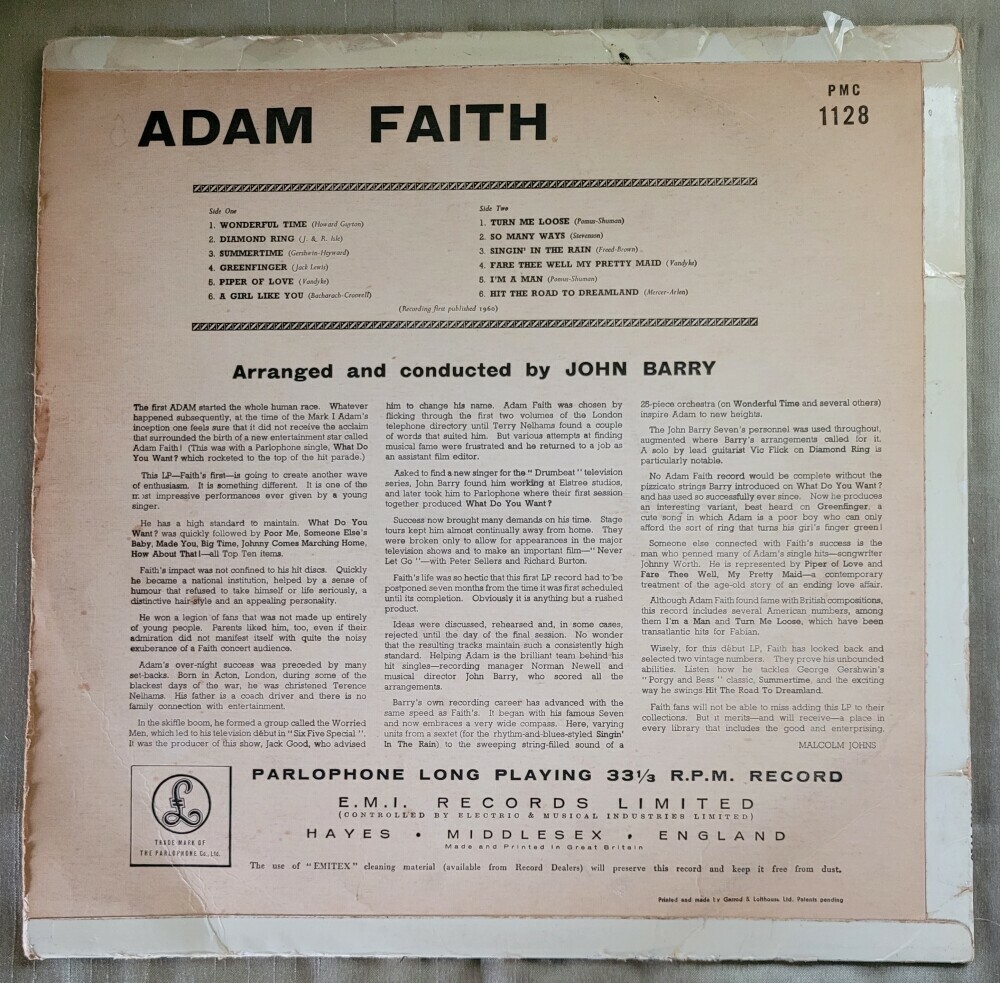

Musicians signed to the label included Humphrey Lyttelton and the Vipers Skiffle Group. In 1959, Parlophone gave a hint regarding where it could expand next by signing Adam Faith who had released three previous singles with other labels. His first single for Parlophone, What Do You Want?, hit the big time, making number one in the UK singles chart in December 1959.

Parlophone’s Golden Era: The Beatles and Beyond

Of course, the story of Parlophone Records is incomplete without mentioning the Beatles. The group travelled to London in early 1962 to audition for Parlophone’s rival Label, Decca. As history reminds us, Decca ‘wasn’t looking for another guitar group’ so they instead signed the guitar group Brian Poole and the Tremeloes. Go figure.

Anyway, and luckily, Decca had recorded the audition. They had either been persuaded to by Brian Epstein or he had paid for the recording. It soon found itself in the hands of George Martin, bypassing Parlophone’s parent EMI, who had no interest in them either. Despite signing Adam Faith, Parlophone was still seen as a purveyor of novelty records – perhaps it was label of last resort.

But George Martin had heard something, and the Beatles were signed to Parlophone in June 1962. This was a turning point for the label, catapulting it into global importance.

Under Martin’s meticulous guidance, Parlophone not only fostered The Beatles but also facilitated the distinctive sound that would become synonymous with the ‘British Invasion’. This era saw British bands dominating the airwaves, with Parlophone at the forefront, amplifying the reach of English pop culture.

The 1960s vibe was immeasurably shaped by the contributions of the Beatles and Parlophone’s other artists. Names like Matt Monro, The Hollies, The Dakotas, and Cilla Black broadened Parlophone’s influence.

During this golden era, the Beatles, EMI, and Parlophone also pioneered advancements in music production. Artificial Double Tracking (ADT) was an experimental technique, invented by Ken Townsend at Abbey Road, which revolutionised the way music was created and consumed. It was this spirit of innovation that enabled Parlophone to push the boundaries of what was possible in sound.

The golden era was a testimony to Parlophone’s knack for identifying and nurturing talent, expanding well beyond the pop and rock genres (and novelty records) that had initially defined its reputation. By 1965 George Martin had quit Parlophone to head up his own recording studio called Associated Independent Recording (AIR). This prompted a major shake-up in the mechanism for hiring producers.

Martin had been merely a salaried member of staff at Parlophone and as such derived no financial bonus from his involvement with the Beatles. His striking out on his own meant that labels had to hire him and on his own terms. In the long run, labels ducked out of this charge, leaving it instead to artists to pay the producer.

The label’s new head was Norman Smith, and he oversaw the gradual decline towards Parlophone’s position as merely a vehicle reissuing Beatles material from 1973 onwards. Soon afterwards Parlophone disappeared as a mark, merging with EMI’s other heritage labels as EMI Records.

Soon enough though, Parlophone was reanimated and in the eighties and beyond, artists such as Dusty Springfield, Tina Turner, Duran Duran, Pet Shop Boys, Radiohead, Supergrass, Blur, Coldplay, Kylie Minogue, Damon Albarn, Conor Maynard, Gabrielle Aplin, and Gorillaz have all released a least one record on the label. As too has Pink Floyd with their 2014 offering, Endless River.

Parlophone’s Legacy and Impact on Modern Music

In George Martin, Parlophone had someone with a keen ear. Considering just three of his successes, Peter Sellers, Adam Faith and the Beatles, it is clear that he knew what he was doing. It was in no small part that Parlophone became a household name because of him. Given the decision by Decca, EMI and other British labels in the early sixties to not sign the Beatles, it is true that his and the label’s willingness to take a risk on the band must have left them exposed. However, as we all know, the Beatles became such a hit that instead of that, nowadays, all talk is about Decca’s decision not to take a chance.

Did the Beatles represent new sounds or were they unconventional artists at the time they were signed? No is the answer to both these questions. However, under the wing of George Martin and Parlophone, they set precedents that dared the industry to evolve. By championing such diversity and experimentation, maybe Parlophone helped nudge listeners towards a more eclectic taste and contributed to a richer global music scene.

What cannot be denied is the impact of Parlophone on music history. The Beatles alone surely indicate that. Perhaps the Beatles’ music is not to your taste. However, I’m sure that many of the technical innovations that they and George Martin instigated are still in use today. Parlophone has not only shaped the musical landscape for generations but has also influenced recording techniques modern artists and record labels.

Warner Music Group bought Parlophone on 7 February 2013, for a sum approaching £500 million ($765 million). This came about as a result of the requirement imposed on Universal Group to allow its acquisition of Parlophone’s parent company EMI. However, Universal was allowed to retain the Beatles’ recorded music catalogue. Consequently, Parlophone became Warner’s third flagship label alongside Warner Records and Atlantic.

So, Parlophone is an imprint controlled by Warner Music now, rather than the quasi-independent label it was under EMI. Of course, there will be the impression of independence; Parlophone has its own A&R set-up and can make decisions as to who they sign, how they are promoted and so on. Ultimately though, I would argue, it fits in with the other labels in the stable rather than being truly autonomous.

Then, of course, there is the Parlophone back catalogue. Warner Group was happy to acquire the label sans the Beatles’ material, so obviously there is merit in having such a prestigious name from the distant and not-so-distant past. To take advantage of its extensive back catalogue, it revamped its marketing approach. Special editions, deluxe releases, and remastered classics became a staple, catering to both new listeners and longtime fans.

Navigating Challenges: Parlophone’s Evolution in the Digital Age

The rise of the internet and digital technology posed significant challenges for the entire music industry, and Parlophone was no exception. As consumer behaviour shifted towards digital downloads and streaming, Parlophone’s new bosses had an asset that for them was a piece in a jigsaw.

One of the key decisions taken by Parlophone in the new age was to embrace the digital revolution head-on. Parlophone recognized that to maintain its relevance, it needed to leverage online platforms and social media to reach listeners.

Nowadays, Warners and the other huge Music Groups, Sony and Universal, are something akin to warehouses; they are huge repositories of music. They offer a wide range of music, categorised in part according to their record labels. Therefore, as part of Warner Group, Parlophone, sets great store in digital distribution platforms such as iTunes, Spotify, and Apple Music to reach a global audience with their part of the warehouse.

As a result, it ensures its music remains accessible to listeners worldwide. This approach is in line with Warner’s attitude at the time they acquired Parlophone. It is interesting to note that in the first decade of the new millennium, all the major music groups appeared reticent to embrace the new technology.

On this point, the shift from physical sales to streaming, necessitated all labels to adapt their revenue models accordingly. Parlophone has not shirked at doing this, focusing on the maximization of revenue through playlist placements, and smart use of algorithms, not to mention releasing new material in a way that optimizes its artists’ visibility and hence earnings in the streaming ecosystem.

Like many other media groups, Warner Group, and Parlophone, has leveraged social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to engage with fans, promote new releases, and build a community around its artists. Content really is king, and the standard of their content has helped Parlophone as they have built a healthy online presence, thus making a connection with a younger demographic.

Many other techniques have been utilised to meet these challenges– from data analytics to innovative marketing campaigns through collaborations with influencers and brands.

Finally, Parlophone has been able to sign up-and-coming artists who had established online followings, the label tapped into new audiences who craved fresh sounds and instant access to music. This has assisted the label’s evolution in the digital age demonstrates its staying power – grief, it was all but dead from 1973 to 1980 – and its ability to embrace technology, to stay competitive and relevant in the ever-evolving music industry landscape.